A Review: Wholly Family -- The Humans, Faith, and Knowing

The Humans by Stephen Karam played at The Alley Theater in Houston on March 1-24. This complicated family drama follows the Blake Clan, an Irish-Catholic family, on a Thanksgiving holiday as they help their youngest daughter, Bridgid, move into her new Chinatown duplex apartment in New York with her boyfriend, Richard.

The stage itself is a dollhouse structure with a metal spiral staircase to the lower floor. As an audience, we can see both the first and second floor. It also acts as an impediment for Momo who is mostly in a wheelchair except for visits to the bathroom assisted by family. Her dementia makes keeping her mobile difficult. The elevator in the hallway is used to ferry her between floors.

When the play opens, Bridgid has plastic bags in hand from the local bodega with things they have forgotten in their moving haze. Most notably, toilet paper. In a smart move by the playwright the bathroom on the upper floor acts as its own aside throughout the production as members of the family go up and down the stairs to use the bathroom. Richard’s otherness is punctuated by the fact that he never goes upstairs to use the restroom throughout the play.

Bridgid’s mother, Dierdre’s, misgivings about the move is evident when she says, “Marriage can help you weather the storm,” soon after she walks into her daughter’s apartment. Her dialogue is laced with Christian marriage concern for Bridgid and her boyfriend. Before they go downstairs to see the rest of the apartment Dierdre hands Bridgid a housewarming gift and tells her to open it downstairs with the family.

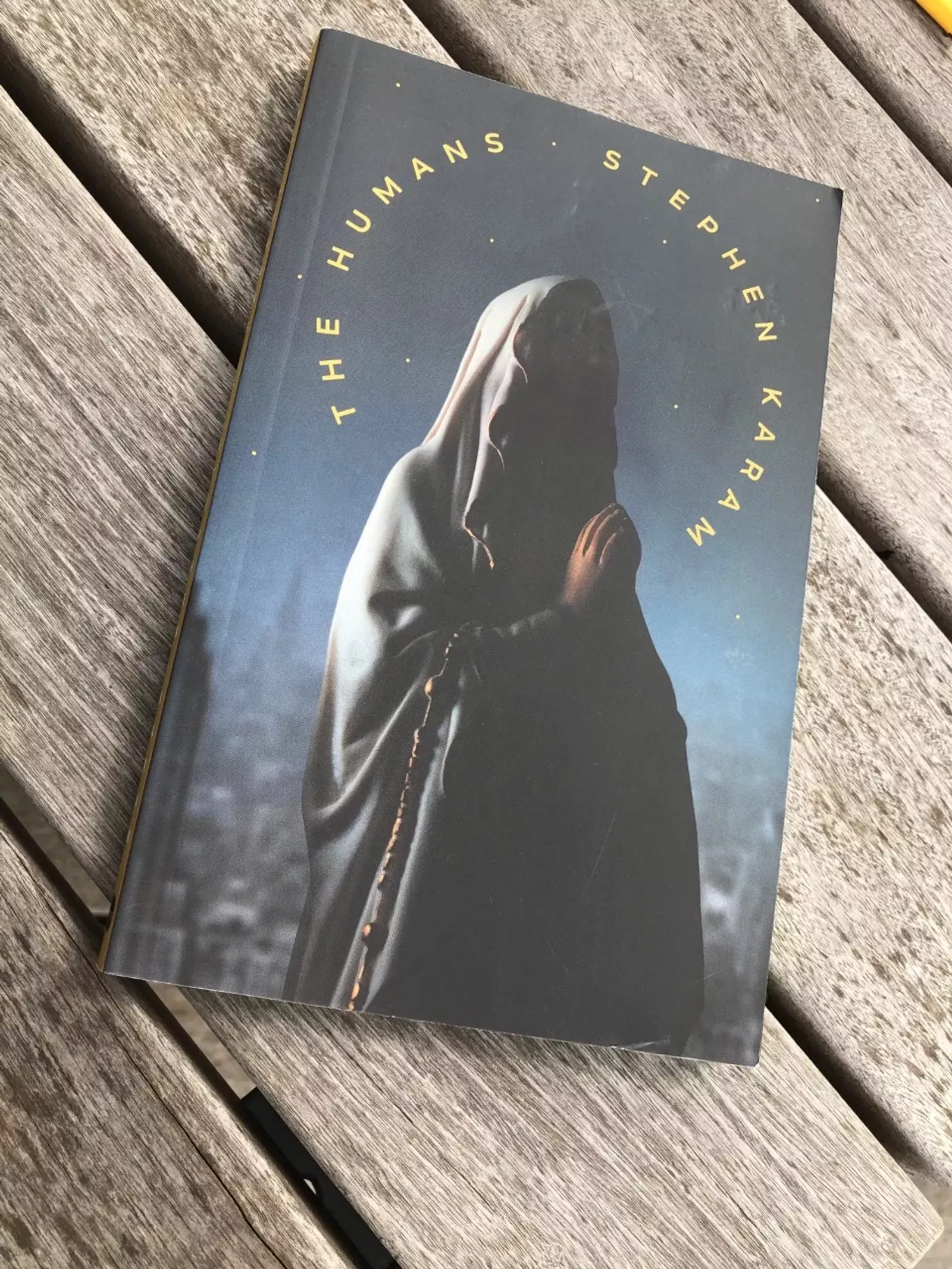

When Bridgid does open it at the table and finds the Virgin Mary Icon she says, “complete with serpent under foot,” where her mother responds, “I know you guys don’t believe, but she’s appearing everywhere...just keep it for my sake, in the kitchen or…just put it in the drawer somewhere.”

“Mom, I will absolutely put this in the drawer somewhere,” Bridgid replies with more love than snark.

“I feel better knowing you have it,” her mother says.

Religion is a large frame for Dierdre, whether it is the Holy Mother or Holy Matrimony. She wants Bridgid to have religious faith too. Still, it seems it’s the way that Bridgid fits the mold that makes Dierdre want her to fill it.

Dierdre’s character is not inflexible though. She is very supportive of Amy, her lesbian daughter who is also there, in her own way as she sends supportive and well-meaning articles to her and comforts her after having recently ended a long relationship. She wants what is best for her daughter and is aware religion doesn’t always offer that for the LGBT community. Much like looking in a mirror, however, she sees a reflection of herself in Bridgid and wonders why it is the opposite of what she imagined.

Even Momo, the only other mother in the room, whose dementia makes her unintelligible manages to express her religiosity in an old e-mail read aloud at dinner, “Dance more than I did. Drink less than I did. Go to church. Be good to everyone you love.” It added a nice texture to the ensemble cast since they were often trying to get Momo to talk more than gibberish ever since she was wheeled into the room. It made me excited to hear what Momo might have said if she were present outside of her illness. Her litany of commands at the end is more accessible than what her daughter-in-law expresses in her own dialogue.

Her e-mail elicits a teary response from the whole family as Momo sleeps fitfully on the couch, the only real piece of furniture in the room that isn’t a folding chair, box, or card table. Even the plates are disposable and printed with a cartoon turkey.

The Virgin Mary Icon never comes back into scene, but it stands as a virtuous ideal. Perfection and goodness as it applies to mothers and even our own families is still hard. Even Mary in the Christian narrative had to watch her son executed as a criminal. Like Mary (or Dierdre), none of us knows how our family’s story is going to shift as it’s handed down.

The truths the play brings forth are many. Everyone has a secret revealed. We are all human with our own problems and concerns, and they never come out easy. For Dierdre, her religion and marriage views are held like a handrail as she deals with trouble in her marriage and finances that are later revealed to the girls by their dad.

His trauma attempts to be expressed in a strange scene at the end where a breaker goes out and the only light is coming in through the hallway outside the lower floor’s entrance. I was confused by this and uncertain of its value. For the father to be left alone to experience what may have been a panic attack or psychosis did not feel genuine. The family was together every other time. In the unseen ending, the family is left to look at themselves and what it means to be together when things are not as they expected, and how they can keep from moving apart as their separate lives move forward, at least until Christmas.