Georgia O'Keeffe: What it Takes to be an Original

I recently finished a biography of Georgia O’Keeffe, and my creative spirit was fed and nurtured by the amazing artist known now as the mother of American modernism. She had grit and was a native free-thinker. As a creative type and free-thinker myself, I’m in awe of someone who maintained a single-pathed focus that rarely wavered. That’s no easy feat.

O’Keeffe’s beginnings gave her the confidence she would need to become a trailblazer. Her childhood on a Wisconsin farm gave her stamina and a love for natural beauty. And of course, the art and music lessons paid off. But perhaps as important were the female examples in her family. Her mother had planned to go to medical school (in the mid-19th century!) but was forced to give it up when the family’s fortunes changed. Her aunts had careers and never married. So it was easy for O’Keeffe to take herself seriously during a time when women were rarely taken seriously.

When Georgia said she intended to be an artist, her family never pointed out that no American woman had made a name in art. Neither did they point out the impracticalities of an artistic life. They simply asked her how she intended to support herself and sent her off to art school. If Georgia intended to be an artist, an artist she would be. Our children should be so fortunate to have us believe as wholeheartedly in their goals.

The self-confidence she learned in childhood would stand her in good stead later on. While at the Art Institute of Chicago, her male colleagues told her that she should sit for fellow artists’ portraits rather than painting her own. She would only be an art teacher someday, one friend said, while he would become an artist (the implication being that women weren’t artists).

Her biggest supporter was her husband and manager, Alfred Stieglitz, but even he doubted each of her new movements. When she began to paint the huge flowers she’s known so well for, he said, “Now what is anybody going to do with those?” and when she turned to painting animal skulls in the desert he encouraged her to turn back from morbid subjects. O’Keeffe let her emotional life lead her art, and didn’t internalize the opinions around her, not even those of her closest confidante.

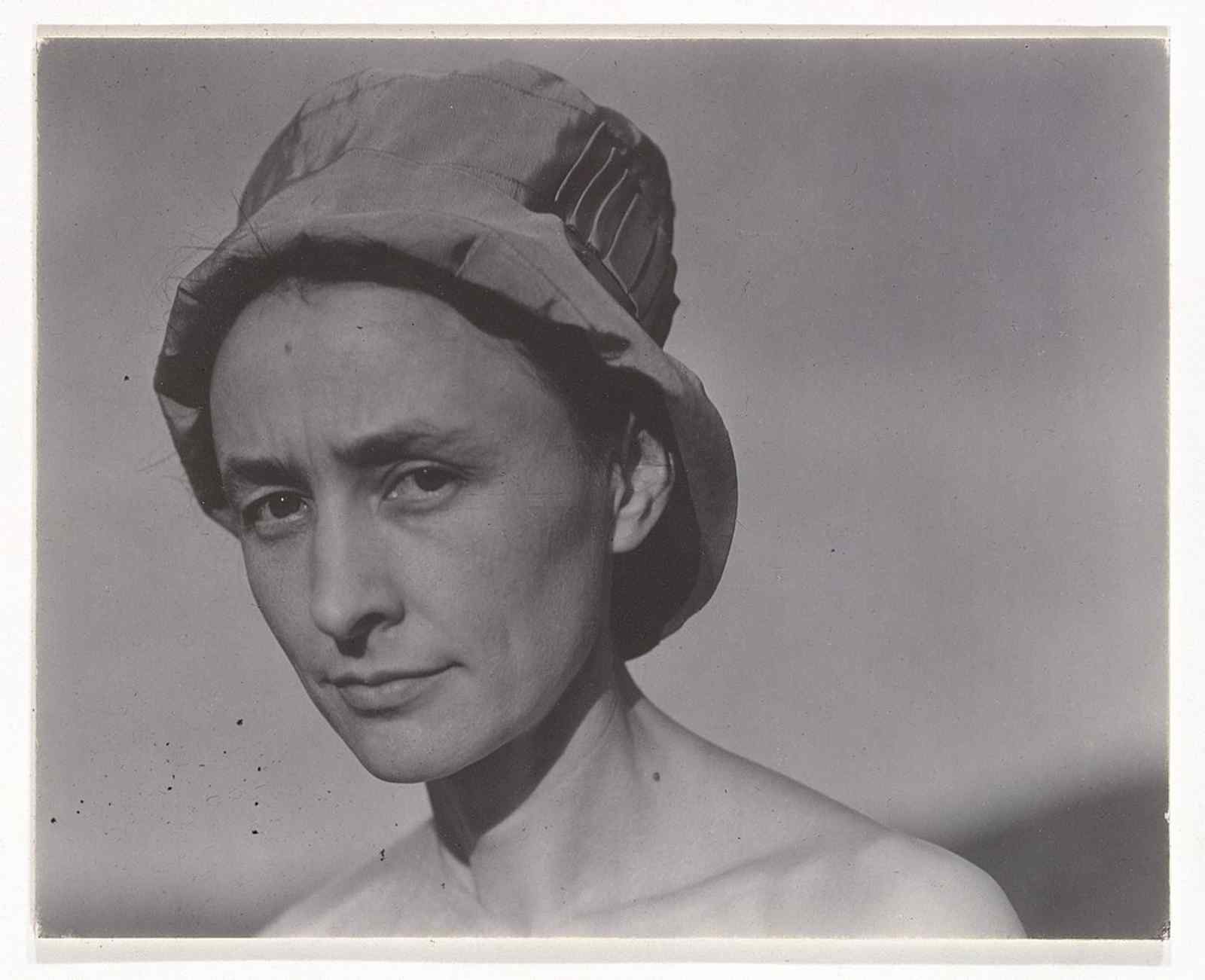

And as her paintings gathered attention, she was increasingly misunderstood. Reviewers ascribed sexual connotations to her flowers and skulls alike, an idea Georgia found ludicrous. She had no objection to being seen as sexual – Stieglitz exhibited a number of nude photos he’d taken of her, and she often painted in the nude. But her flowers were a response to the skyscrapers which she felt were detracting people’s attention from the exquisite beauty around them. The large scale flowers would make them take another look. There was nothing sexual in O’Keeffe’s intent, but she decided not to counter the reviews. People would make of her art what they would. It wasn’t her job to tell people how to interpret her art, only to give them art worth interpreting. The woman knew who she was and what her life was about.

Georgia knew what she needed most – solitude, and lots of it. Her extroverted husband was bewildered by the days or weeks she needed to paint alone, but he gradually accepted it until at the last she was spending almost half the year alone in New Mexico while he remained in New York. It’s not that she didn’t feel a constant tension, as she tried to balance the needs of her husband and the needs of her art, but her art always remained her north star.

O’Keeffe did occasionally experience periods of doubt; she had two such profound periods – she stopped painting for a few years after art school and later on, when she went against her husband’s business advice by contributing a mural to a museum without payment, she had a breakdown (possibly exacerbated by her husband’s infidelity). She couldn’t paint the mural, ended up in the hospital with a “nervous breakdown” a/k/a severe depression and didn’t paint for a couple of years after.

Her success continued after that but O’Keeffe wasn’t alone. She had a number of artists, writers, and philosophers in her corner, some well-known – Ansel Adams, Aldous Huxley, the Lindberghs and D.H. Lawrence, to name a few, and other less famous friends who cheered her on. Her curator husband was especially helpful, publicizing her art and managing her career so she could be free to focus. Their relationship was often troubled, but they had a deep connection that buoyed her. And of course, there’s nothing like success to build a little confidence (one of O’Keeffe’s paintings sold for more than any previous American painting before).

By staying true to her vision, O’Keeffe was able to deliver a feminine touch that was new and captivating to the art world. And her dream-like New Mexico art, gave rise to other streams of abstract art in America.

Many of us at Oasis can take something away from O’Keeffe’s life story. There’s the balancing act of managing people’s expectations while standing firm in her beliefs and lifestyle. There’s the tension between the freedom of blazing her own trail and the resulting isolation. Living one’s own vision is its own reward, but often comes with more tangible payoffs – in Georgia O’Keeffe’s case, original, exceptional art.