Sending Student Teachers to Juvie Hall: Training Teachers to be Successful with the "Tough" Students

Dr. Dennis Fehr, a tenured emeritus professor at Texas Tech University, was named Texas Art Educator of the Year in 1999 and Art Educator of the Year for the Western Region of the United States in 2000. In 2005 he developed a student teaching program for his undergraduate future teachers in an institution of juvenile incarceration. It ended with his retirement in 2012, because no one wanted to continue it. Here is his story:

I was kicked out of school in eighth grade. One fine day I decided that hiding a squirt gun under my desk and firing away at our science teacher’s fly was a good idea. I tallied several handsome shots before he glanced down and noticed that things were amiss.

I outgrew my childish ways and, ironically, became a teacher. I understood the problems that many of the “bad kids” endured at home—the substance abuse, neglect, and violence. I knew what they were going to do before they did. One guidance counselor, in an awkward attempt to compliment me, referred to my classroom as his “dumping ground” for these students because I was able to reach them.

After a mostly enjoyable decade of teaching middle and high school in the public system, I concluded that I had something to say about how these students learn. I acquired the requisite graduate degrees and became a professor of education—a teacher of teachers.

My student teachers usually came from a distinct demographic. There were days when I could have sworn they all were 20, white, and named Christie. Almost all had been “good kids” who hoped to teach kids like themselves, baby birds with open mouths waiting to be fed facts and figures. On the other hand, they were petrified of the “bad kids,” the dark-skinned, poor kids. My students, now at the ends of their programs, had no idea how to teach them.

Most of my fellow professors fit the same demographic, just older; they had acquired advanced degrees, and in the process had failed to learn how to teach the “bad kids.” They were, with the best intentions, passing their ignorance down. I realized that we were not going to progress until we professors taught our students how to teach children who were different from them, the children most in need of what they had to offer.

I contacted the Lubbock County Juvenile Justice Center about starting a student teaching program. It was an easy sell. They said I was the first person from the university to contact them about anything, ever, and they loved the idea.

Convincing the university was a different story. Not surprisingly, my colleagues opposed it. “You’d be putting our students in harm’s way!” Parents and boyfriends objected. One parent’s unwitting response: “What could my daughter possibly learn there that would help her in a school?” Not one accepted my offer to tour the facility. I had uncovered a case study in class prejudice.

Frustrated, I asked our department chair, a wise and experienced leader, to tour the facility with me. She learned that the ratio of special needs inmates in the population was one in four. So were we locking up this population because they were inconvenient? We met an 11-year-old who had robbed an ice cream truck using his brother’s pistol. We met a student who, prior to her arrest, had been sleeping in the neighborhood park to avoid unwanted advances from her mother’s boyfriend. Her crime was stealing cereal.

We saw that guards were stationed throughout the hallways a few yards from the classroom doors. If you have ever seen a high school security guard attempt to run across a campus, you will know that juvie hall is safer than the average high school.

Above all, my department chair saw the humanity in these youth. She saw how much they needed us. She was quiet until we reached my car. Then she spoke, almost in a whisper, “You’re right, Dennis. Bring your students here.”

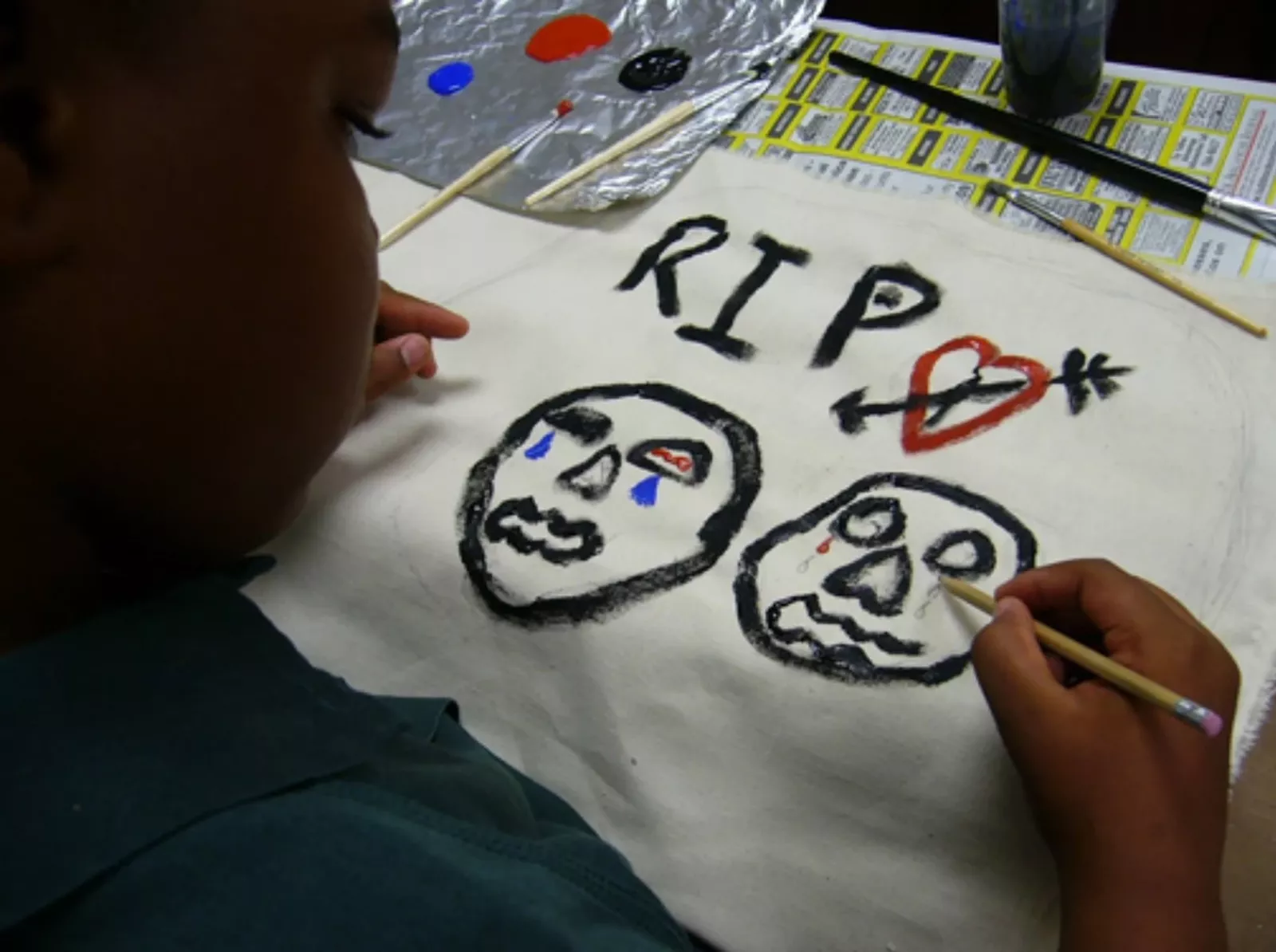

So I took them there, year after year. We always took a field trip first so they could see what my department chair saw. This softened them. Over time, they connected with their students; they were startled to realize how like them they were. Some asked me if they could continue to volunteer there after the course ended. Yes, they could. Was there any way they could apply to teach there? Yes, there was.

This course produced the highest anonymous student evaluations of any course I’ve ever taught:

“I’m so much better prepared for the public schools.”

“I feel like now I can handle any student.”

“Best course I’ve taken at this university.”

Negative evaluations? Year after year, not one.

Adam Gopnik points out in the April 15, 2019, issue of The New Yorker that we are beginning to question the effectiveness of incarceration. Perhaps it is time for our nation’s education colleges to question their curricula. We can contribute substantively to the healing of our divided country by creating teachers who understand how much students who are not “like them” are like them. If we can enable our teachers to connect with our neediest students, the time could arrive when our juvenile halls are all but empty.