The Oasien Life of Georgie Franks Hunter

I’ve pondered a lot and questioned a lot since my mother was first diagnosed with glioblastoma, a rare form of brain cancer, and even more since her premature death at a very young and vivacious 66 years old. Mom attended Oasis with me a few times, and she fit right in here.

Most people won’t remember the words you say or even necessarily your specific actions. They will, however, be very in tune with how they instinctively feel when they think of you or see you. No pause is needed. We don’t consider all of an individual’s past actions and words and then evaluate our feelings towards them in a rational, systematic fashion. There is only an immediate feeling of warmth (or not) toward that person. My mother had a knack for giving that feeling of warmth to almost all who knew her.

It was the accumulation of many acts of kindness and words of encouragement throughout the years that cultivated that very feeling that those who knew her get when they think of my mother. It’s the smile she wore when she saw them. It was the infectious guffaw she shared liberally. And laughter was my mother’s forte. (Which she would have promptly encouraged me to pronounce “fort” as that was her preferred pronunciation. Both are correct – I’ve checked). It’s the empathy she exuded when she was with anyone during times of their suffering. It’s the sense of self-worth she gave to all by her demonstration that she saw you as the human you are, as her equal.

So how do we decide how to celebrate one’s life after they’re gone? Our best bet is to emulate how the person lived while they were here. Mom frowned upon the usual morose atmosphere of funerals (although that didn’t stop her from playing the organ at many of them.) She scoffed at the usual banality of “ashes to ashes, dust to dust” and other Bronze Age melancholia. Mom would want us to face her passing with a celebration of her life, not an occasion to get together and cry (although I’ve been doing plenty of that and reserve that right to continue to do so with hopefully decreasing frequency.) Mom would have felt right at home being trailed by a New Orleans jazz band and second line, and she certainly wouldn’t have had any qualms with us in the sanctuary listening intently enjoying a Coke and Sazerac.

If you wanted to truly celebrate my mother I would encourage you to defend those who are treated as anything less than equals; work hard at all you do, knowing that you can be as fiercely independent as my mother, building the life you want to live as she built hers. Don’t feel obligated to settle for anything plain when you can and should aim for extraordinary. Recognize the beauty in all you see. And lastly do your utmost to instill that feeling of warmth she gave so freely in all who allow you.

At first glance, this may feel like a blog post about my mother, Georgie. Yes, her name's in the title, and yes her eulogy precedes this all-too-brief vita, but she would have been the first to tell you that it's not about her. Nor was it ever about her, as almost all mothers will tell you. She had trouble recognizing her selflessness as a virtue; it was a lifestyle. One she learned watching her mother drive the farm-worker's children daily to school in her own vehicle because the bus refused to pick them up out of what could only be described as poorly-disguised racism. She internalized the meaning from making a difference my grandmother made in the lives of those children, and all the lives they touched subsequently. She learned that her hands could solve human problems and enhance lives by watching her mother do just that.

She loved teaching children to sing and play the piano. She directed choirs and played the organ and flute. She donated generously to the ACLU, Carter Foundation, SPLC, Union of Concerned Scientists, the Democratic Party, and a dozen other organizations devoted to human well-being. Raised within a society wrought with patriarchy instilled her with an initial sense of self-doubt. After a lifetime of being told what she couldn't do, she set out to figure out what she could. She traveled. She ran the family farm. She hosted parties with friends from around the country. Growing up in a small Wyoming town, she learned the value of community, but suffered from its limitations as well. She fiercely loved the people at the local senior center, the daily lunches with them and steering the conversation into politics. She was a life-long democrat in a sea of life-long republicans. She wasn't afraid to ask a man if he'd talk like that to her if she weren’t a woman. My mother hung her hat on the importance of human dignity and the basic tenant of equality.

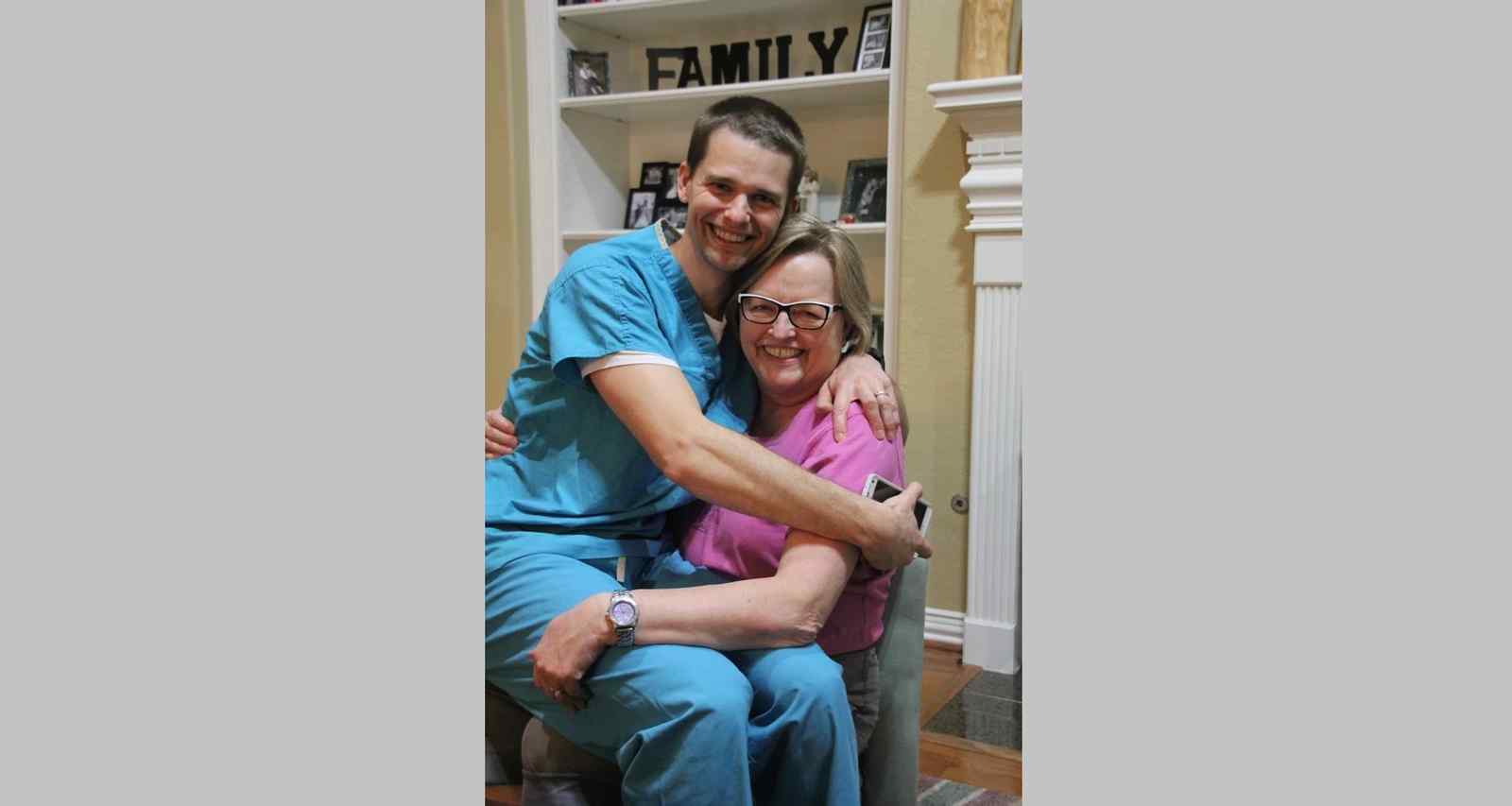

I'd like to think that, after I matured all-together too late, I doted on her like any loving son would. Like all good mothers, she never stopped teaching me. It's only appropriate that one of her best lessons from life was given at the end of it. As she said when discovering that she wouldn't live much longer, "Shit happens." In those two words she reminded me of the fragility of life and the importance of doting on all fine things while you can, especially one's mother.